Ancestors of University of Manchester medical students diligently studying diseased biological tissue through microscopes in the Old Medical School. On display as part of the Subvisible Bodies exhibit. (UPC/2/337)

An exciting new display in the Rylands Gallery showcases items from the University of Manchester Library’s medical collections alongside intriguing artefacts from the Museum of Medicine and Health (MMH). Subvisible Bodies is a whistle-stop exploration of medical microscopy in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Objects, printed books and archives relating to the Old Medical School at the University of Manchester, one of largest and best-equipped medical schools in England in the 1890s, have been brought together for the first time.

Stephanie Seville, Heritage Officer at the Museum of Medicine and Health, notes: “I am ecstatic to be able to make available objects to add to the wonderfully curated display at the John Rylands Library. My role is within the Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, supporting the University’s Social Responsibility agenda to embed public engagement activities in research and education. I help to look after and make accessible a collection of over 8000 medical instruments and equipment which form part of the University Collections. Dr Peter and Julie Mohr give their time generously as volunteers and have been instrumental in helping with this collaboration.”

‘The Artifical Eye’: Microscopes and Medicine

Our medical special collections hold the first best-selling work on microscopy, Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1667). Hooke’s show-stopping volume is famous for its minutely detailed engraving of a flea, as well as beautifully described depictions of the tip of a needle, frozen urine and fish scales. Hooke hailed an instrument that artificially ‘enlarged’ and ‘rectified’ the senses, enabling the viewer to explore new worlds with a delicacy not afforded by the naked eye.

The microscope is shown with an oil lamp and water-filled glass flask, which Hooke used to diffuse light and illuminate his samples. Hooke’s volume is fairly hefty and so not currently on display. Digitised images can be viewed via LUNA. (SC13288C)

Though the microscope was used in scientific research from the 17th century, it was not until the mid-19th century that it was applied to the burgeoning practices of clinical and laboratory medicine. Until the mid-19th century microscopes were largely custom-made and adjusted through trial and error. Advances in optical science enabled the reliable replication of precise instruments.

Subvisible Bodies includes an impressive Hartnack & Prazmowski brass microscope from the MMH collections alongside a wide variety of specialist paraphernalia, including a drop bottle for staining specimens, microscope slide labels and a ‘dissecting kit’ made in Manchester.

Microscopes designed by German inventor Ernst Hartnack were used by pioneers of “germ theory”, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. (MMH, 2011.309-3)

Microscope Dissection Kit, Flatters & Garnett Ltd, c1920s

The careful preparation of biological material using delicate cutting and probing tools was a time-consuming skill. Section cutting, drying, dissecting, bleaching, staining and fixing all had to be learnt. (MMH, 2011.309-3)

‘Subvisible Bodies’: Humans and Disease

The anatomy of the visible body was rigorously explored on the dissecting table for many centuries. But the intricate structures of organ tissue and microorganisms were not as accessible. Microscopy facilitated new disciplines of medicine based on scrutiny of how the body and disease worked on minute, ultimately cellular, level.

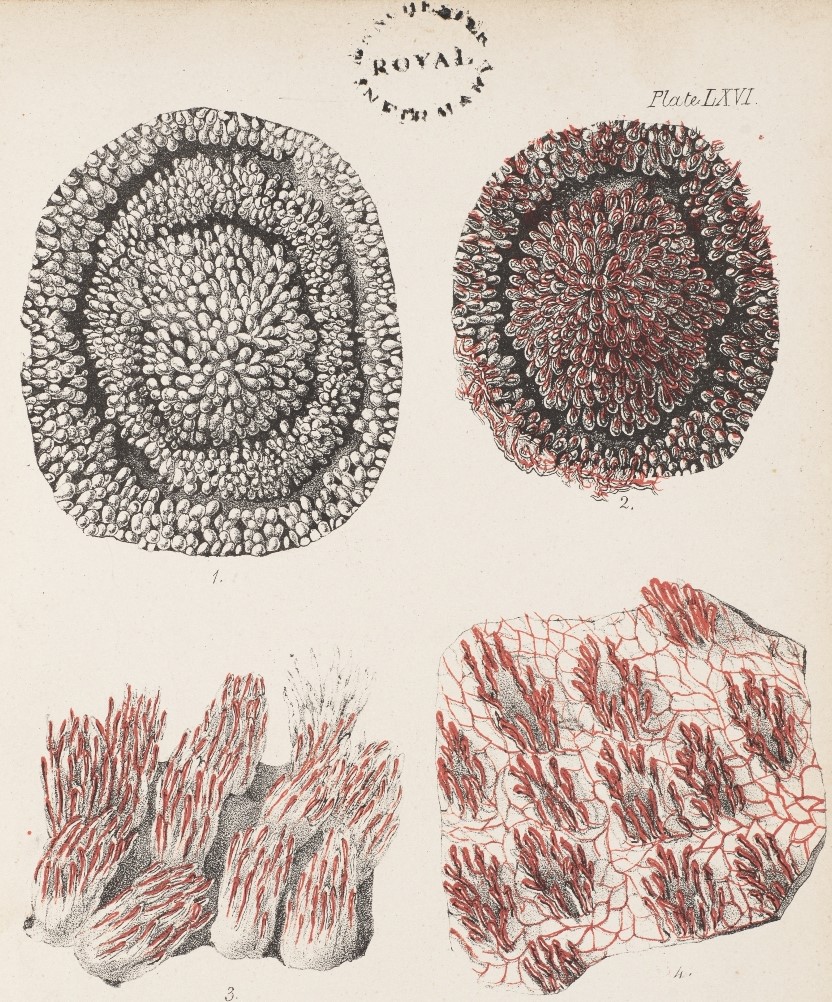

The histology notebook of John Stopford is a fascinating example of this. Stopford’s intricate histological illustrations (pictured below and on display) were drawn when he was an 18-year-old medical student at the University of Manchester. They demonstrate the importance of skilled medical illustration at the time.

Stopford became head of the department of anatomy at the University of Manchester at the age of just 30. He went on to become the first Manchester medical graduate to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and became Vice-Chancellor of the University in 1934. (John Stopford Papers, GB 133 STO/3/3)

Working with printed and manuscript materials, it can be easy to forget that advances in medical science during this period relied on the supply of real human and animal tissue. In the 19th century such material was not always acquired by consent and often came from disenfranchised individuals.

It is important to bear this in mind when contextualising medical collections, particularly when the provenance of objects like microscope slides can be difficult to trace. Displaying microscope slides alongside the ‘finished product’ illustrated in medical books allows these connections to be made, though the slides in the exhibit are animal tissue only.

Microscopy allowed fresh examination of things studied by the naked eye since ancient times. Human tissues (like the mucous membrane of the tongue shown below) could be illustrated in vivid detail, aided by the advance of colour printing throughout the 19th century. From the liver to lymph nodes, spleen to semen, a number of printed anatomy manuals on display explore the microscopic human body in health and disease.

Hassall was a prominent 19th-century physician and microscopist who earned his fame in the rapidly developing field of public health (and caused quite a scandal with his ‘revolting’ microscopic illustrations of London drinking water!). (Medical Printed Collections post-1800, C2.3 H16)

The items described here (and many more) are on display in the Rylands Gallery at The John Rylands Library until Spring 2020. Drop by and explore for yourself.

With thanks to the Museum of Medicine and Health for kindly lending objects from their amazing collections. Thanks also to the University of Manchester Imaging, Collection Care and Visitor Engagement teams.

Printed items on display have been catalogued as part of a Wellcome Trust funded project, more information here.

0 comments on “Subvisible Bodies: Medical Microscopy in the Rylands Gallery”