John McCrory writes:

Opposition to the Boer war was deeply unpopular, with any newspaper taking a critical stance suffering from public hostility, declining circulation and charges from politicians and rival publications of sympathising with the Boer enemy. Given such commercial, political and even personal pressures, amidst what J.E. Taylor, proprietor of the Manchester Guardian, termed the “Mad fury of the English populace”, it is unsurprising that few newspapers offered a dissenting voice (and none as consistently as the Manchester Guardian). While Taylor’s backing allowed C.P. Scott and the Manchester Guardian the freedom to condemn the Government’s policies in South Africa, other editors were not so fortunate.

The letters below are from Albert Cartwright, editor of the only Liberal English-language newspaper in Cape Colony, the South Africa Daily News, and then correspondent for the leading Liberal newspaper in London, the Daily Chronicle. In the first sent to J.A. Hobson (who had recently returned from South Africa after reporting for the Manchester Guardian) on 26 Dec 1899, he describes his shock and confusion over the resignation of Henry Massingham, the anti-war editor of the Daily Chronicle, following pressure from its managing director, Frank Lloyd:

What a shocking figure the Lloyds cut! …Massingham retired because Lloyd wanted him to refrain from criticising any officers of the Government. Good heavens! What’s coming over the nation? An incident such as that sounds more like Paris under the Dreyfus madness, than sober, sensible England.

Cartwright continues believing that Alfred Milner, Governor of Cape Colony and a chief architect of the war, had used his considerable influence to silence criticism:

I suppose it was showing up Milner’s suppression of dispatches that brought things to a climax; doubtless Milner or his friends brought pressure to bear through Asquith or some other leader.

Reflecting concerns about the war voiced by many writers in the Scott correspondence, many of whom were familiar with South Africa, Cartwright continues:

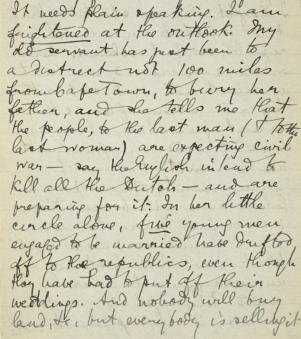

I am frightened at the outlook. My old servant has just been to a district not 100 miles from Cape Town, to bury her father, and she tells me that the people, to the last man (& to the last woman) are expecting civil war- say the English intend to kill all the Dutch- and are preparing for it…

If this thing drags out for six or nine months more I fear it cannot be kept within its present limits.

Outraged by the treatment of Massingham, Cartwright relinquishes his role as the Daily Chronicle’s representative. He then details to Hobson some suggestions on future arrangements, proposing to telegraph one newspaper which would then forward his cables to other subscribers- ideally six radical dailies across the country.

With the great disparities in numbers and budget between the pro and anti-war newspapers, Cartwright sought to amplify the anti-war message as efficiently as possible:

Will you believe that in suggesting this I don’t want more money (I would do it for just the same fee as for one paper) but because I wish to see [Cecil] Rhodes and Co fought, squarely and persistently, in the Home Press?

In a later letter to C.P. Scott, sent on 9 Jan 1900, he expands on the same theme, again voicing his fear that this war in South Africa will intensify sectarian division between the British and Dutch settlers:

When one sees the amount of money spent on cables by the London Tory press, in sending to England every silly tale, every foolish innuendo that can be worked up against the stubborn and conservative and not very interesting but believe me neither malicious nor unkindly Boer of the back-veld, one sometimes feels that it is hopeless, that the country must just drift till it is a Colonial Ireland, and that the best thing one can do is to clear out to a land which is spared the curse of race-hatred.

Scott had asked Cartwright in an earlier letter whether he wished to act for the Manchester Guardian in South Africa. While initially declining, awaiting further news from Massingham- to whom he felt a strong loyalty- Cartwright tells Scott:

I am more proud than I can tell you at the idea that the old “Guardian”, for which like most Manchester men I have a respect amounting almost to awe, thinks my services worth having…

Along with other exiles from the Daily Chronicle, H.W. Nevinson, Harold Spender and Vaughan Nash, Cartwright did later work on behalf of the Manchester Guardian. While acting in this capacity in April 1901, he was prosecuted by the authorities in South Africa for a seditious libel, tried before a judge and jury, and sentenced to a year’s imprisonment. He had published a letter from ‘A British Officer’, which claimed that Lord Kitchener had sent secret instructions to units in the field to take no prisoners (also publishing Kitchener’s denial of the charge). This letter first appeared in the Freeman’s Journal in Dublin and extracts were reprinted in The Times, yet only Cartwright was prosecuted for its publication. With most of Cape Colony under martial law during 1901 (Cape Town, where Cartwright was based, was excepted at this point), and the British engaged in a bitter guerrilla war with the Boers, such accusations were deemed highly inflammatory.

While he was imprisoned, a subscription fund for Cartwright’s family was set up by the South Africa Conciliation Committee, to which C.P. Scott contributed, alongside other newspaper editors. On his release Cartwright was refused permission by the military authorities to leave Cape Colony and return to Britain, the Secretary for War stating: “It was not deemed desirable by the authorities in South Africa to increase the number of persons in this country [Great Britain] who disseminated anti-British propaganda”. His case was the subject of a debate in parliament in April 1902, with members from both the Liberal and Conservative parties, including David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, protesting at the arbitrary exclusion from this country of a British subject. This restriction was lifted a month later, allowing Cartwright to return to Britain.

Cartwright returned to South Africa in 1907 to edit the Transvaal Leader, the newspaper which published articles by Mahatma Gandhi, in which Gandhi wrote demanding civil rights for Indians in the Transvaal. A supporter of the Indian cause in his columns, in January 1908 Cartwright acted as an intermediary between J.C. Smuts, the former Boer General turned Colonial Secretary, and Gandhi, when the latter was imprisoned over the issue of registration for Indian workers. As a personal friend of Gandhi’s, Cartwright helped gain his consent for Smuts’ proposals.

In repeating the charge made against Lord Kitchener, and thereby questioning the reputation of the British army in the field, Cartwright’s decision to publish resulted in his imprisonment. His experience reminds us of the sacrifices often made by journalists offering uncomfortable opinions, accusations, or truths during the heightened tensions of war.

On Thu, 26 Jan 2017 at 10:39, John Rylands Library Special Collections Blog wrote:

> Jessica Smith posted: “John McCrory writes: Opposition to the Boer war was > deeply unpopular, with any newspaper taking a critical stance suffering > from public hostility, declining circulation and charges from politicians > and rival publications of sympathising with the Boer e” >

I think he’s my great great grandfather